It seems like every week there is another news article or clip about someone in Court for stealing, from small goods to multi-million dollar Ponzi schemes. Theft is a common sin of people today, rich or poor. Sadly, little has changed over thousands of years, and will not change either until the Lord returns.

Because theft is a perpetual problem, in addition to laws which punished harm against people and sought to protect their essential dignity, the Law also contained various laws to protect the property of people. These laws covered payments to replace the harm caused by theft, negligent acts, and when borrowing was involved.

The first category of crimes relating to property involved theft (vv.1-4). Stiff penalties were applied for theft when the animal was killed or on-sold. If you stole a sheep, you had to pay back four, if you stole an oxen (a bigger animal requiring plenty of training to pull your plow, so a more harmful theft), then you had to repay five (v.1).

If the animal was in the thief’s possession when caught, the penalty was double repayment (v.4). This recognised that the harm was only temporary, since the Israelite was reunited with his wealth.

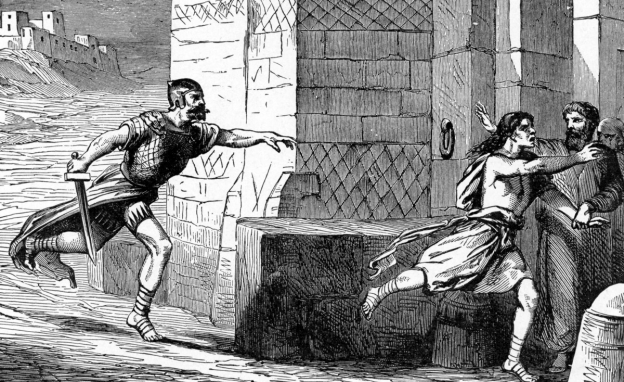

But these laws also protected the thief from a guaranteed death sentence. At night, if a thief attempted breaking and entering, the homeowner could think they were actually there to commit murder. In that case, a homeowner was innocent of killing to protect life and property (v.2). But if this happened during the day, then killing was not justified (v.3).

Finally, because considerable debts were owed for theft, sometimes someone could not pay. In that case, it was not reparation at $20 a week, but instead the thief would be sold into servitude to repay the debt (v.3), and treated according to the laws for servants and slaves in chapter 21.

The second category of property crimes were those of loss due to negligence (vv.5-6). For instance, if an owner of animals carelessly let his flock eat someone else’s crops, he had to repay the loss (v.5). If he set a fire to clear land for grazing and through carelessness or accident (eg, wind gust) caused a wildfire and property damage or loss, he had to repay the loss (v.6).

The third category related to borrowed or entrusted property (vv.7-15). In a world without banks, safe deposit boxes, and Hirepool, your neighbours were often entrusted with your prized possessions. In those situations, things could go wrong.

For instance, while in their house, your things could be stolen (v.7). The thief was still liable as before. If the goods were recovered, then a fine of double the value was required.

But what if the thief could not be found? Perhaps it was all a story from the borrower or trustee to “liberate” the goods for themselves. In that case, the trustee was to submit himself to God and the elders to investigate if he was the thief or telling the truth (v.8). If he was defrauding the owner, then he had to pay double for the loss (v.9).

Sometimes, animals disappeared. If the borrower was not to blame, he was to swear before God that he was not to blame, and the owner had to take his word (vv.10-11). But if he knows it was stolen (and by implication, failed to stop it), he was to pay to make it right (v.12). If there was evidence the animal was attacked by a wild animal, he should present that evidence to clear himself of wrongdoing (v.13).

The final example is where an animal was borrowed. If it died without the owner present, the borrower owned the risk and had to make payment (v.14). If the owner was present, the borrower was not liable. And if he had hired the animal, then the owner was being compensated for the risk in his hiring fee (v.15).

These examples show that justice goes beyond punishment to putting things right. A repentant thief got a steep discount – only twenty percent extra repayment (Lev. 6:4-5). Rich or poor, they paid. Repentant or not though, the victim of the crime was put right financially…but the thief still had a right to life. It is my property, yes, but it is only my property.

This principle should extend to how we treat others’ property. If we break it, we should fix or replace it. We should not make the other party suffer the loss for us. Justice in God’s eyes sees things put right for the victim.

When we are reminded of God’s justice, it makes even starker the riches of God’s mercy. We are all thieves, and owe God our lives as the punishment for our sin. But God showers us with his love and mercy, because Christ paid the restitution we could not to satisfy God’s justice. He frees us from the penalty of sin to love God and love each other, respecting what is theirs.