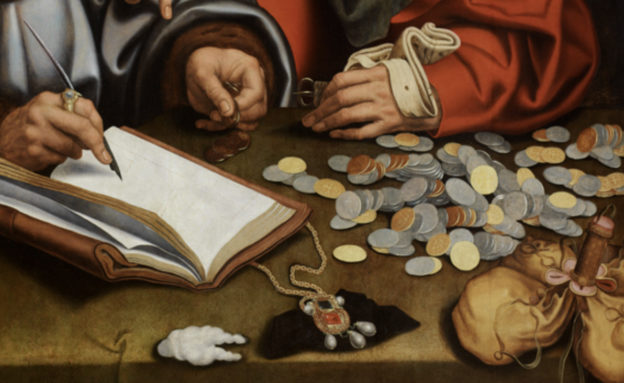

Something was rotten at Mount Sinai. After forty days of waiting for Moses to reappear, the hard hearts of Israel had led them into sin, denying the God who had brought them out of Egypt and fashioning their own golden calf as an idol. A deity of their own making and their own tastes, who asked nothing and did nothing as the sinful “good times” rolled.

As the People partied below, Moses and God communed above. But God saw the idolatry and immorality of Israel at the foot of Mount Sinai, and his righteousness demanded a response. While judgement was the just punishment, God established the circumstances for Moses to intercede for Israel on the basis of God’s nature and his covenant love. In the same way, Jesus intercedes for us despite our sinfulness, so we can enjoy forgiveness and fellowship with God.

In the first six verses of chapter 32, God’s People made a golden calf to worship in the place of the true and living God. Without the leadership of Moses among them, they were left to their own sinful devices and embraced sin.

God, who unlike the golden calf can see all things, told Moses in verse seven to “Go down, for your people, whom you brought up out of the land of Egypt, have corrupted themselves.” What God saw was so offensive that he does not want to identify himself with Israel in their current state; the people now become Moses’, who Moses brought up from Egypt.

God’s disgust and distancing is because of Israel’s corruption. This shows the seriousness of sin. It is not a minor dislike or an inconvenience, but a corruption of both what is good and our very being. The people disobeyed God and worshiped a golden calf (v.8), corrupting themselves.

But while God is distancing himself from God’s People’s current sinfulness, he does associate Moses with them. God could have sent fire from heaven to consume Israel then and there, but instead he sent down Moses to intervene.

This is clear because in verse nine, God describes Israel as “a stiff-necked people.” This is a reference to animals who refused to accept a farmer’s yoke and discipline, and resisted the farmer’s will. God sees Israel as refusing his command and discipline.

Since God’s People will not listen to God, perhaps it is time to start again. God reveals his anger at sin and the punishment it requires by suggesting Moses leaves him alone so that “my wrath may burn hot against them and I may consume them, in order that I may make a great nation of you” (v.10). At least Moses has developed enough from his earlier distrust and disobedience of God as the ingredients for a new batch of God’s People.

At this point Moses takes the opening provided by God to intervene on behalf of his people, and intercede for the sinful Israelites below. He does so by making three arguments why God should not destroy the Israelites.

Firstly, Moses reminded God that he had chosen the Israelites and “brought [them] out of the land of Egypt with great power and with a mighty hand” (v.11). God had chosen to love them as a father loves an adopted child, and acted to save them.

Secondly, Moses reminded God that he saved Israel to glorify his name. If he destroyed Israel, Egypt and the nations might question God’s motives for saving Israel from slavery (v.12), which would affect his reputation.

Thirdly, Moses reminded God of his covenant promises to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, to number their offspring like the stars of the heaven (v.13). God’s promises to the Patriarchs could not be abandoned by God, because God always keeps his promises.

Because of Moses’ interceding, God “relented from the disaster that he had spoken of bringing on his people” (v.14). God heard Moses intercede for his people, and in his grace and covenant love did not destroy them, just as intended.

So if God never intended to destroy Israel, why set up the scene for Moses to intercede? Because this situation taught them and us of our need for a mediator to intercede on our behalf with God for our sins.

Our sin corrupts us and separates us from God. God cannot associate himself with or approve of sin. Someone must stand in the place of sinners and intercede on their behalf, asking God to remember his election, his glory, and his promises.

While Moses interceded effectively in this situation at Sinai, he could not perfectly intercede for all sinners, because he is a sinner too. But Jesus can intercede perfectly, because he is both God and Man, and was sinlessly obedient unto death.

Jesus interceding for us, both in his High Priestly Prayer (John 17) and now at the Father’s Side, effectively reminds God of his election of many to salvation, the glory that comes to God for his salvation, and the covenant promises made and fulfilled in Christ.

Thank God for our glorious mediator, Jesus, who intercedes so effectively for us!